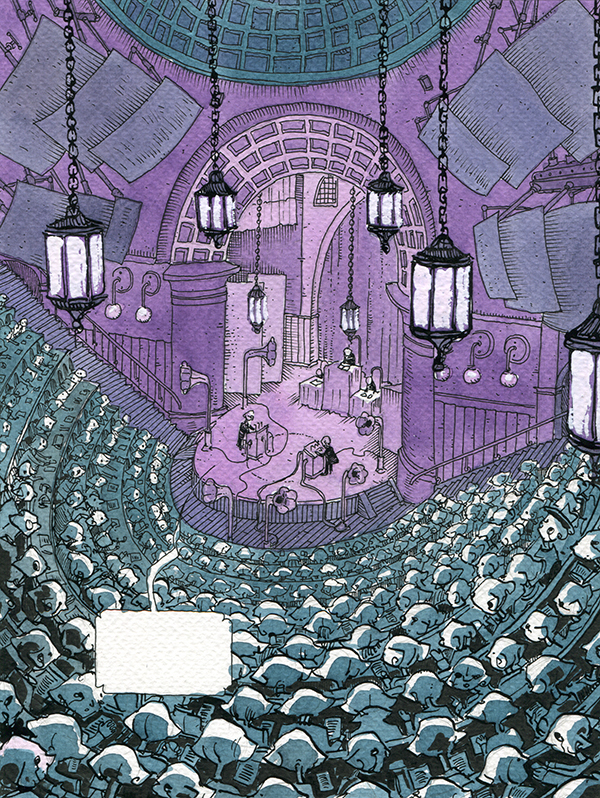

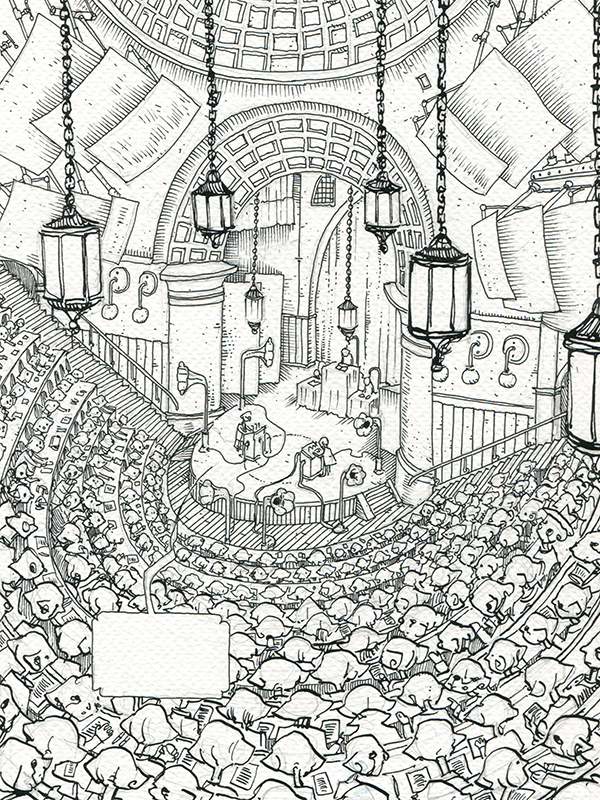

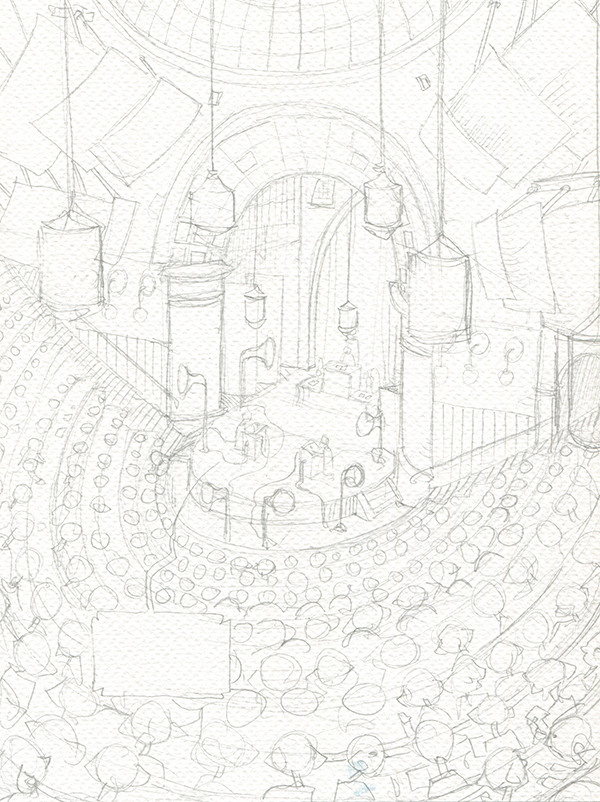

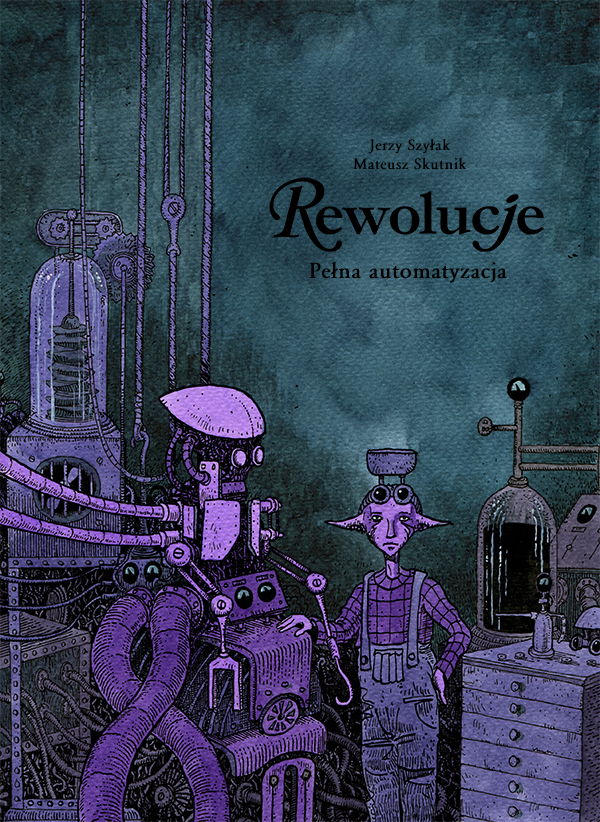

Rewolucje: Integral release announcement

July 13, 2016

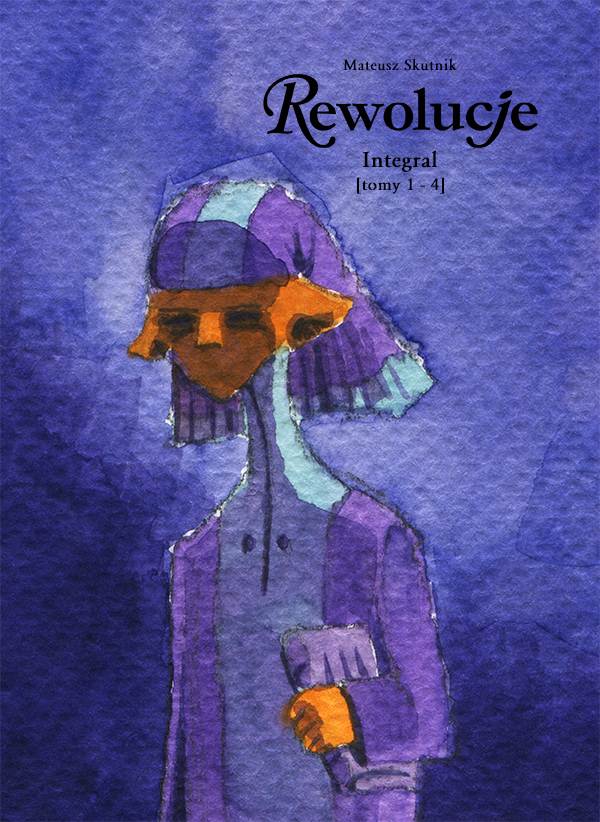

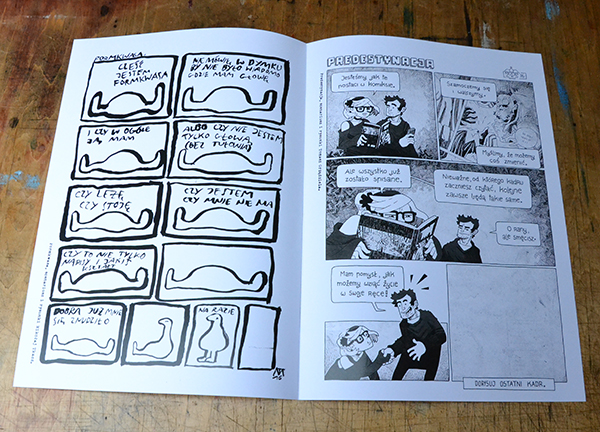

Dla odmiany dobre wiadomości, zwłaszcza dla czytelników Rewolucji którym brak pierwszych, egmontowskich tomów. Do druku właśnie poszedł integral tej serii, składajacy się z pierwszych czterech tomów. Łącznie dwieście stron komiksu opatrzonych nową okładką.

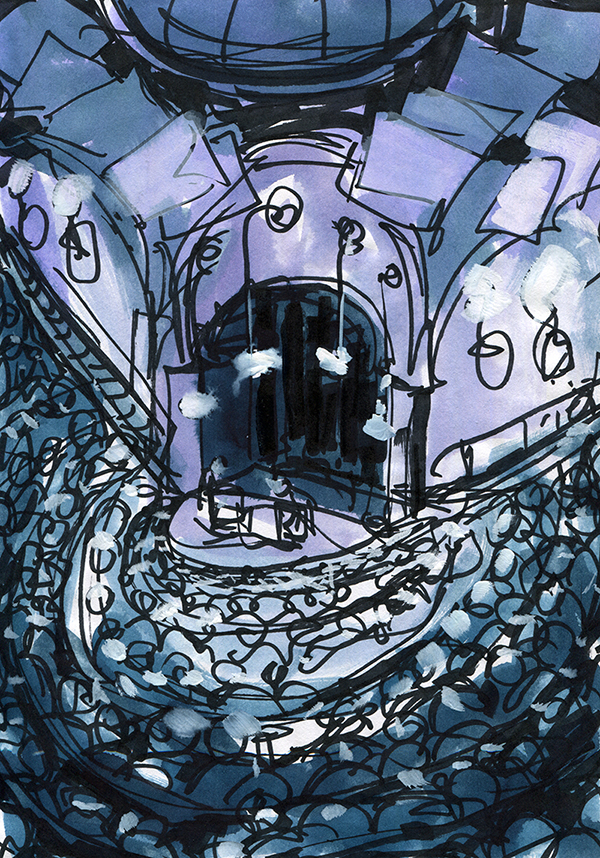

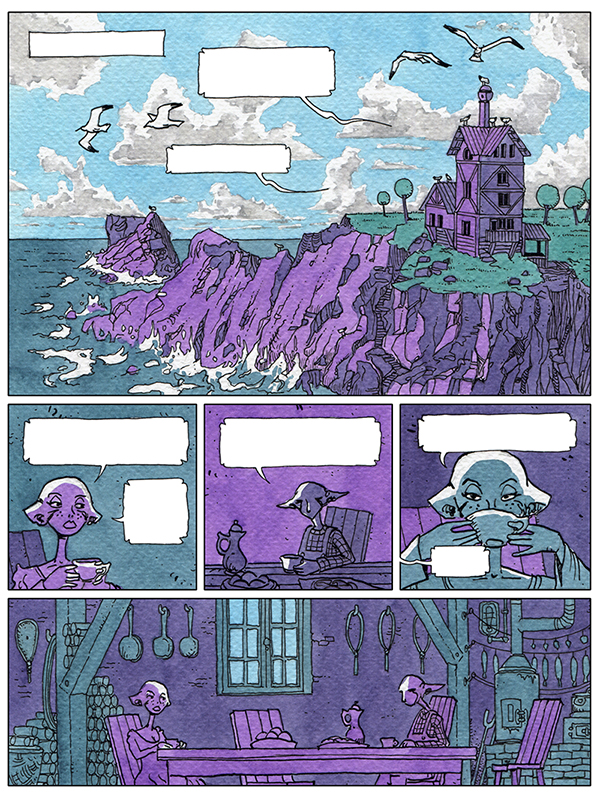

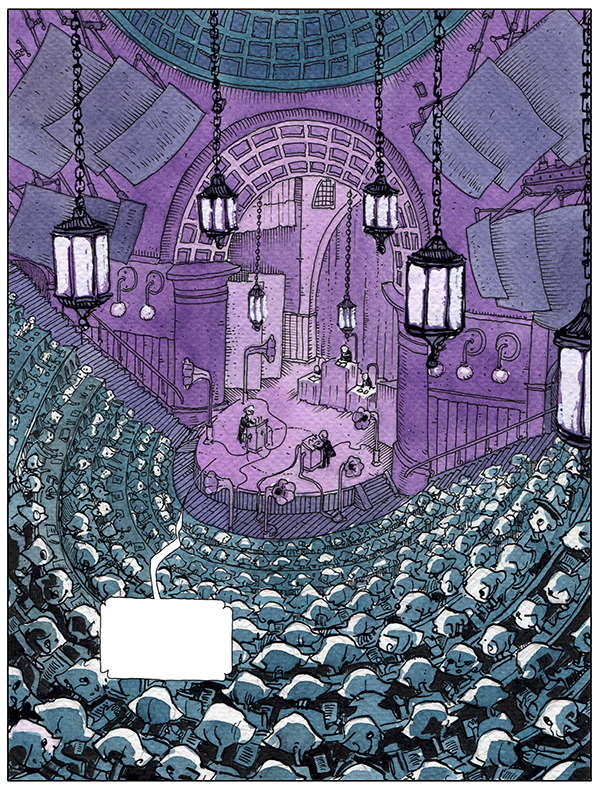

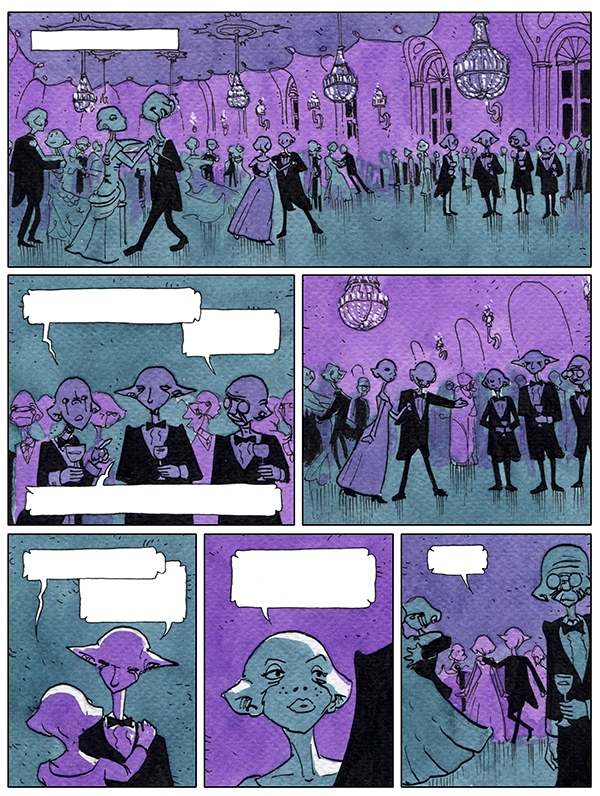

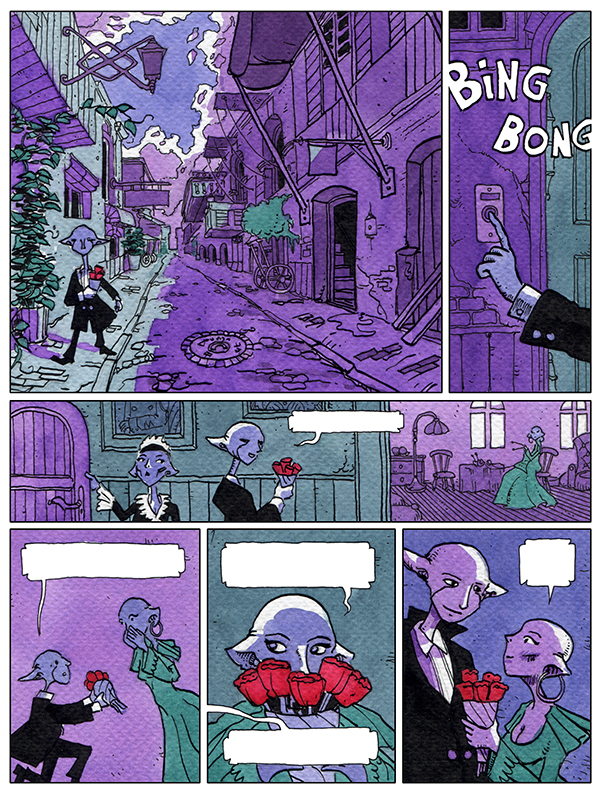

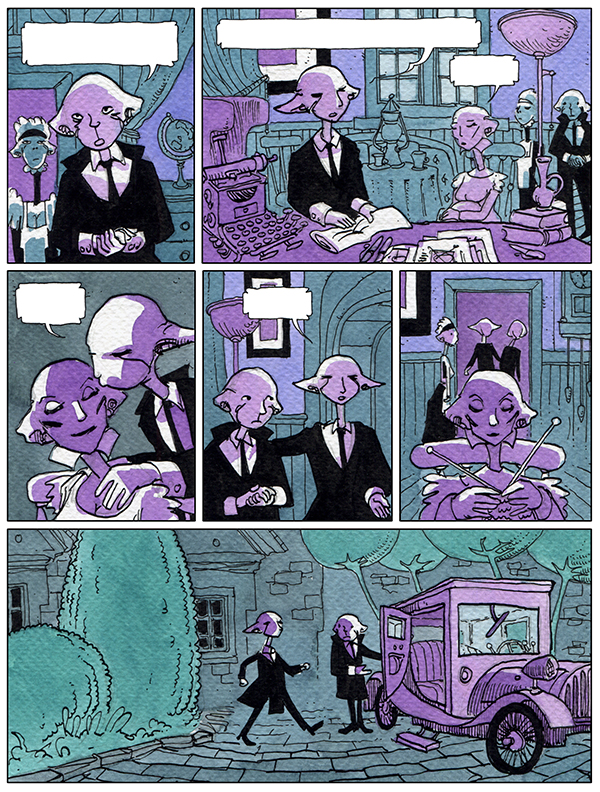

Te cztery tomy składają się z pozornie niepowiązanych ze sobą krótkich historii, które, gdy spojrzeć na nie z pewnej odległości, układają się w zamkniętą, mozaikową historię.

Po przeczytaniu tego integrala polecam ponowne przeczytanie tomów 6-9, w których znajdują się drobne odniesienia do tej pierwszej tetralogii.

A teraz najlepsze: premiera integrala Rewolucji wypada już 29 sierpnia 2016!

//–

[Info techniczne na marginesie: ostatni miesiąc spędziłem przygotowując cały materiał na nowo do druku. Skanowanie, czyszczenie ramek i dymków, i co najważniejsze, nowe, zunifikowane liternictwo na wzór nowych tomów z tej dekady (patrz: Rewolucje 9 i 10).]

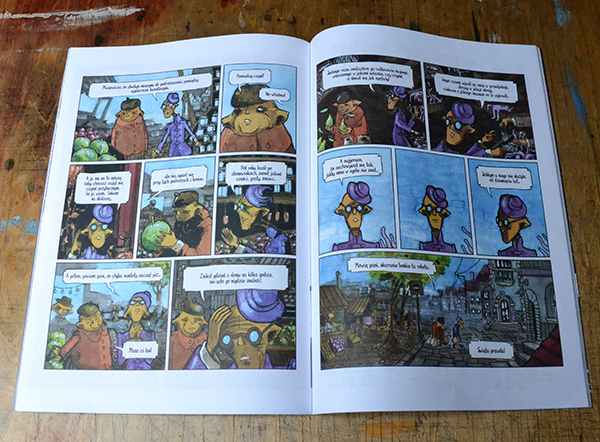

Komiksową serię Rewolucje Mateusza Skutnika należy uznać za godny hołd złożony erze silnika parowego, epokowym wynalazkom i wielkim wizjonerom. Mamy tu do czynienia z oryginalnymi opowieściami z pogranicza literatury steampunkowej oraz suspensu, z elementami grozy i kryminału. Twórca przewrotnego cyklu wykreował na jego łamach niepowtarzalne uniwersum, wypełnione wybitnymi jednostkami, a także ich nieszablonowymi dziełami. W ósmym tomie (W kosmosie) pozornie oderwane od siebie wątki mocno zazębiają się ze sobą, a jego osią fabularną jest podróż w stronę gwiazd.

Komiksową serię Rewolucje Mateusza Skutnika należy uznać za godny hołd złożony erze silnika parowego, epokowym wynalazkom i wielkim wizjonerom. Mamy tu do czynienia z oryginalnymi opowieściami z pogranicza literatury steampunkowej oraz suspensu, z elementami grozy i kryminału. Twórca przewrotnego cyklu wykreował na jego łamach niepowtarzalne uniwersum, wypełnione wybitnymi jednostkami, a także ich nieszablonowymi dziełami. W ósmym tomie (W kosmosie) pozornie oderwane od siebie wątki mocno zazębiają się ze sobą, a jego osią fabularną jest podróż w stronę gwiazd.