24 hour comics day 2015

October 12, 2015

Did I ever tell you the definition of insanity?

Well, yes, yes I did. Twice already. Here and here.

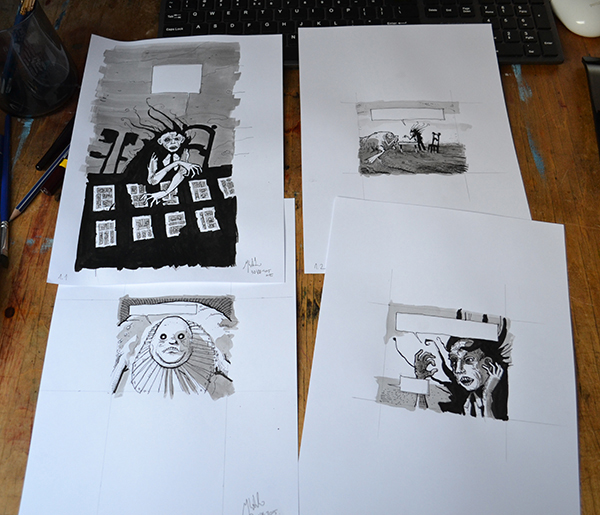

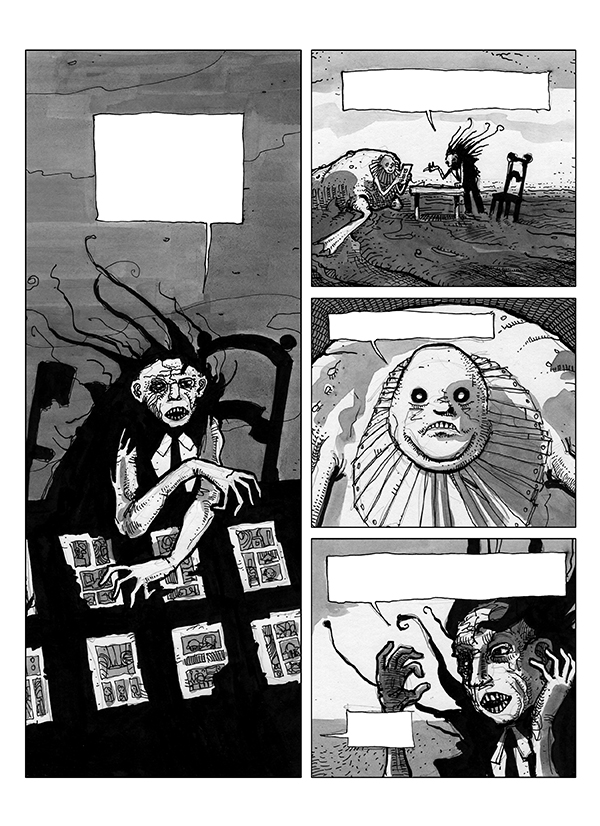

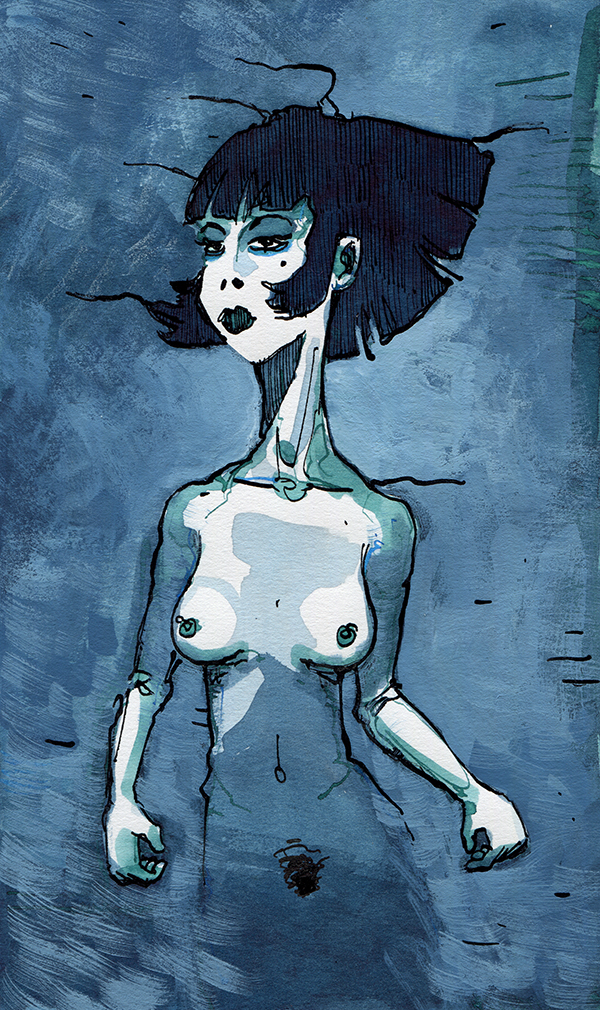

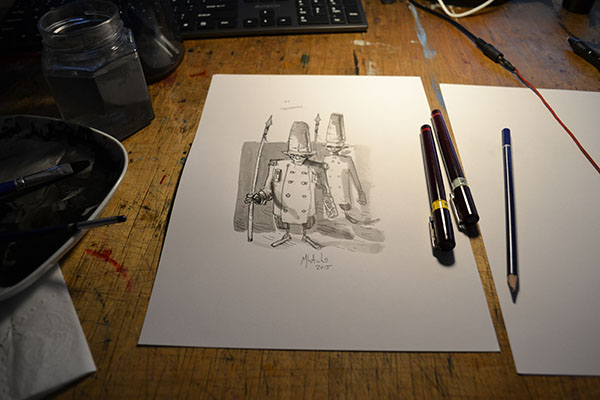

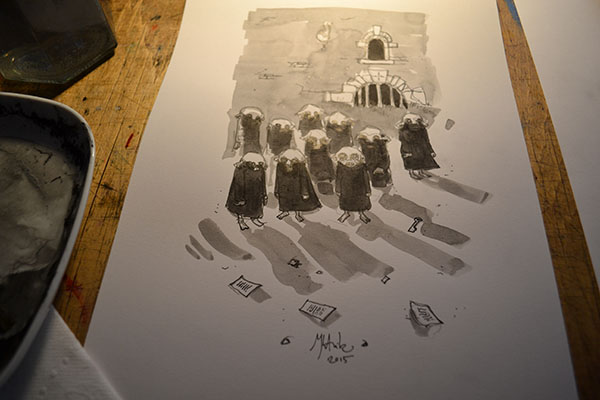

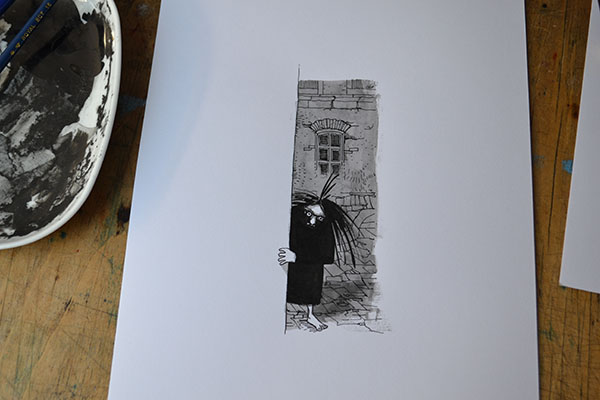

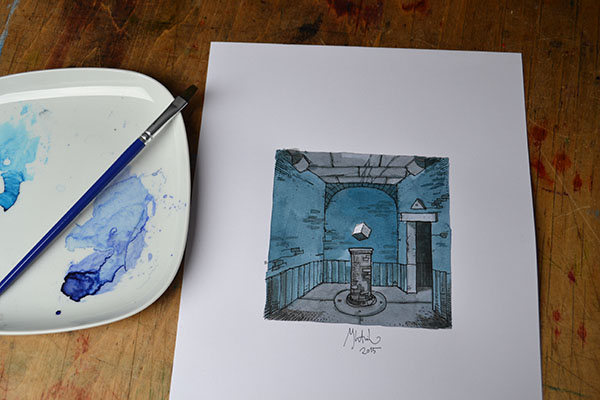

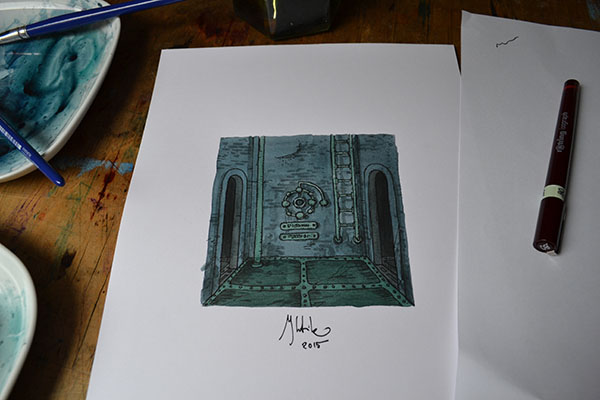

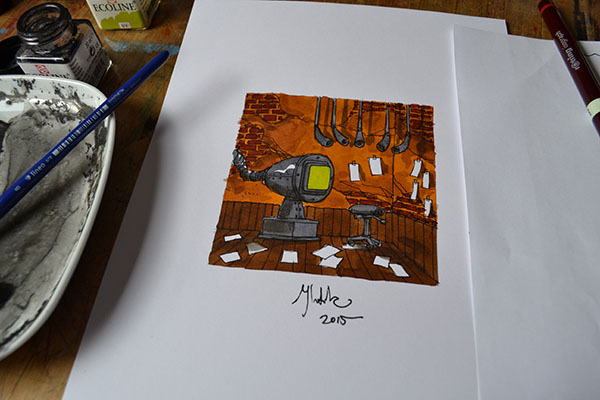

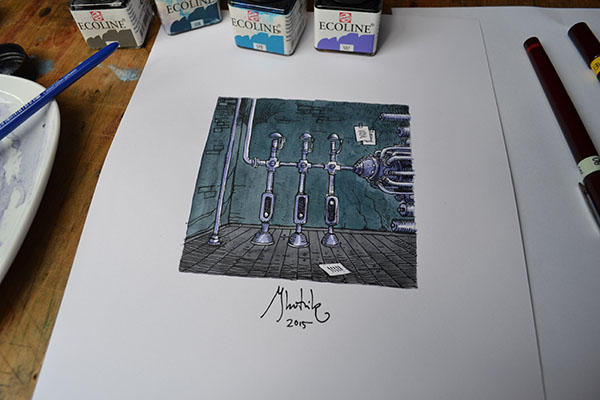

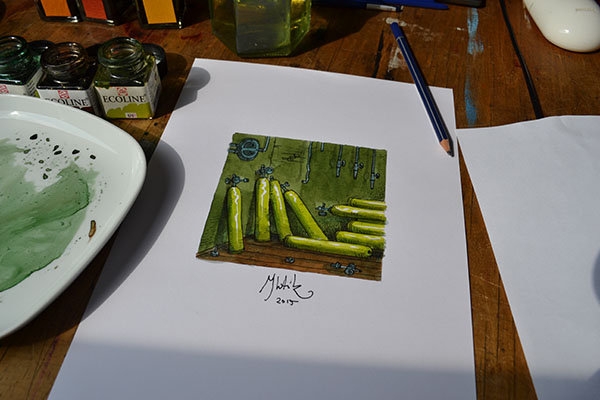

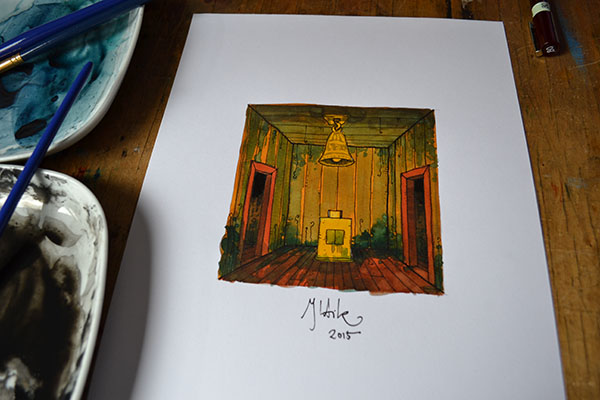

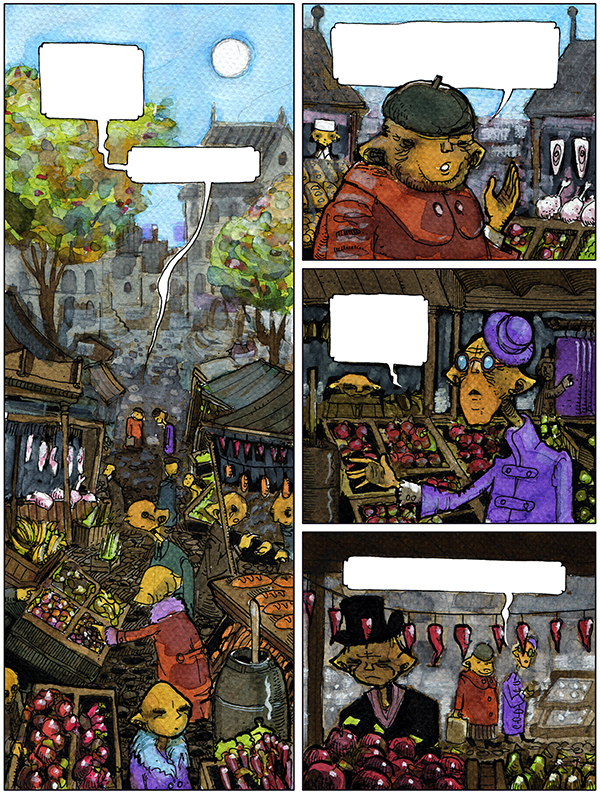

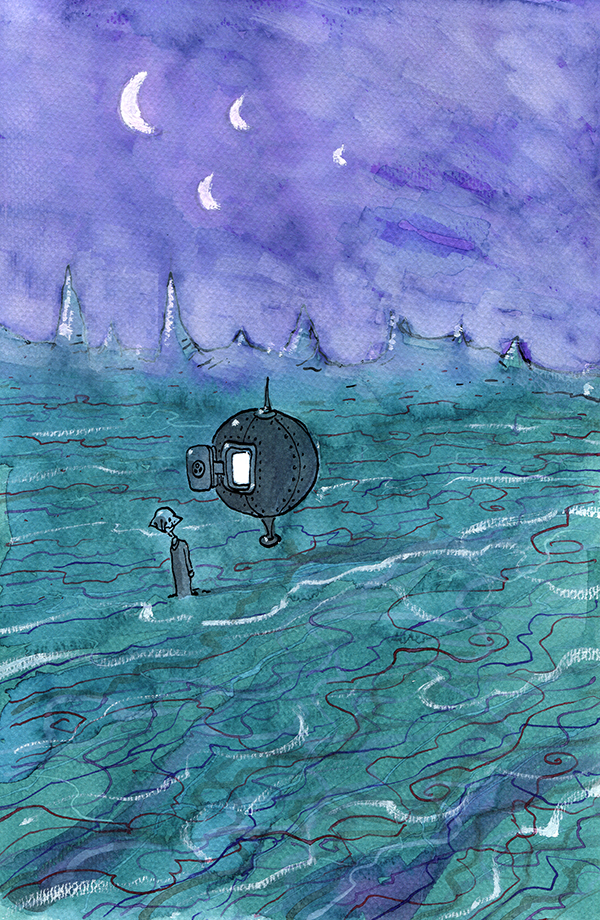

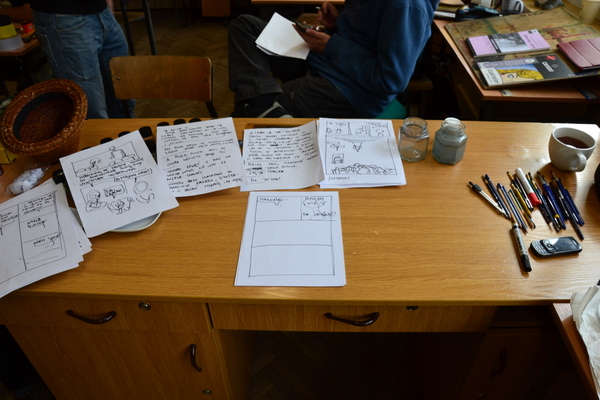

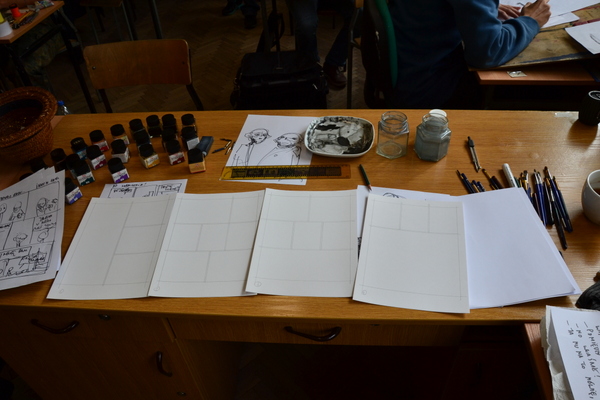

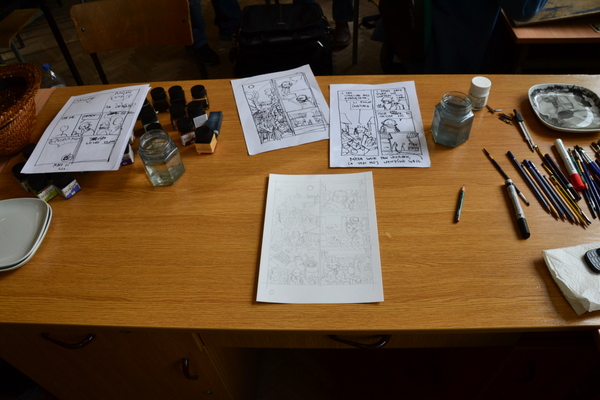

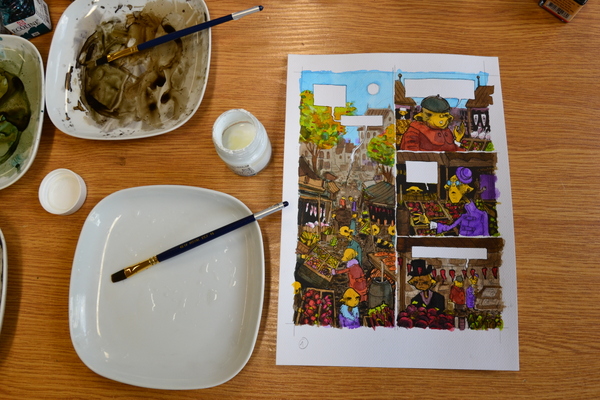

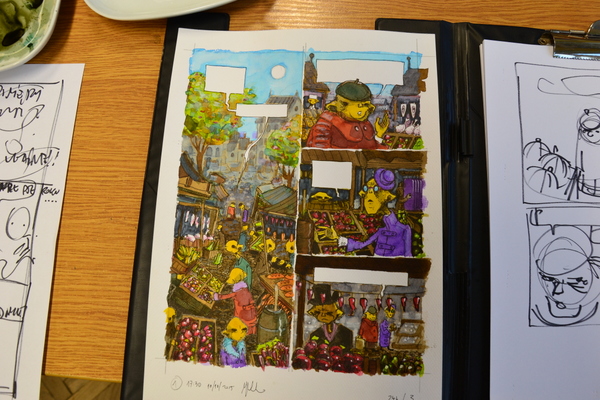

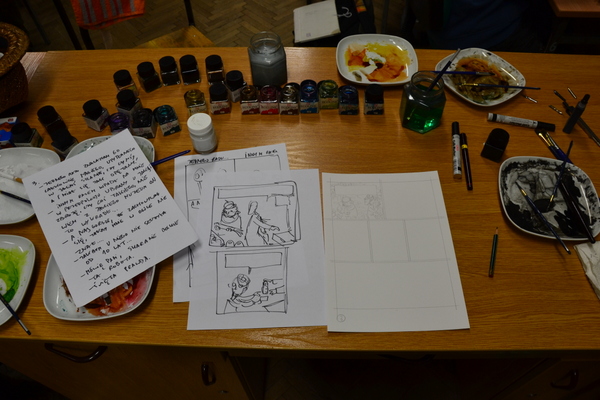

My take on this challenge is a bit different than what Scott McCloud proposes. Yes, I did create a 24-page comics in 24-hour span, that was on my first attempt in 2011, and right then this particular challenge lost it’s meaning because of the fact that I achieved it. Since then my take on this whole idea is this: create for 24 hours. The main condition is time, not number of pages. I’d rather create few pages but of high, printable quality, than a 24-page half-assed, rushed through comics that will be good for nothing actually. And that’s what I’ve been doing since 2011. This year I wanted to create a 4-page Rewolucje short, as I was asked by Andrzej Baron for something for his Znakomiks magazine. Last year I learned that creating one Rewolucje page takes about 6 hours, so the timing was perfect. The first page however (shown below) took me 7.5 hours. Luckily, that was the main establishing shot, most detailed opening of the short. Latter pages were simpler to create and I finished all of this around 5:30 A.M. Since I had few hours left I also created a cover for a 24-hour comic book anthology, as asked by the publisher and organizer of the event. You can also check it out below. Besides that I’m posting photos I’ve been taking more or less hourly through entire 24 hours (well, 20, since I split after 8 A.M. when I had literally nothing more to do). So here it is. The insanity.

Taki już ze mnie przyziemny chłopak, czyli uwagi o ewolucji Rewolucji.

Taki już ze mnie przyziemny chłopak, czyli uwagi o ewolucji Rewolucji.