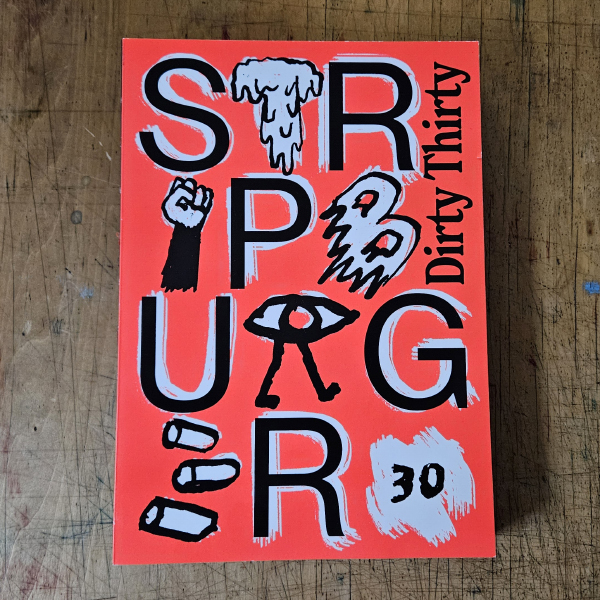

Daymare Cat 10-year Anniversary

June 27, 2023

download this game for free from itch.io | play online on Newgrounds

read original release post from 2013

~

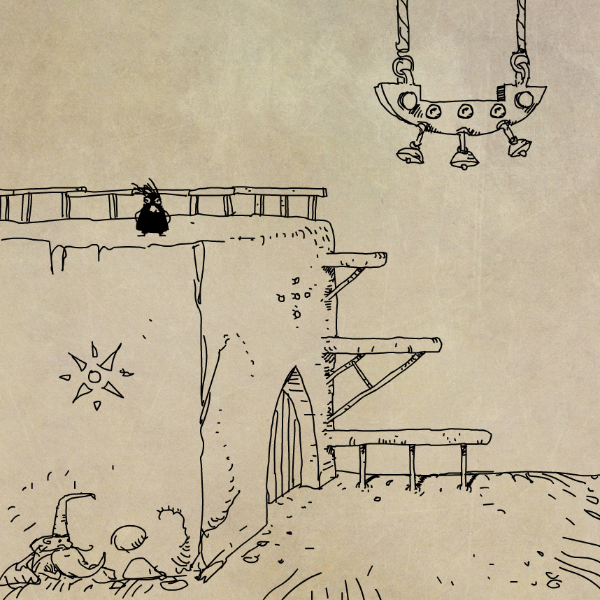

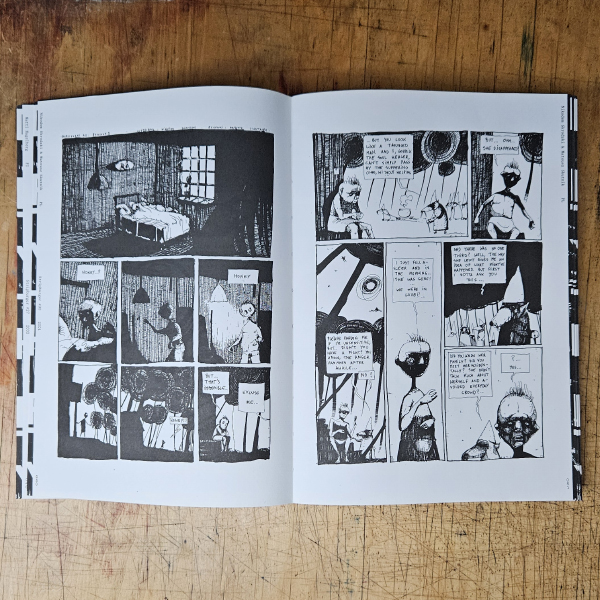

“Daymare Cat is a gorgeously sketched exploratory platformer that feels like a simple adventure game. The platforming here isn’t particularly challenging, but almost every hand-drawn scene is worth witnessing.” – said some by now non-existent indie game review website in 2013.

~

The main character of this game is Cat Jahnke, and I’m not talking about the in-game little girl, but the singer and songwriter, who created the song that this game is all about. This is the reason why this particular game stands out in my catalogue of games. Hats off to you, Cat. Let’s just hope that you’re right in the song, and things will finally get better.

~

Meanwhile, it’s 2023. How is it possible that it’s been 10 years already… Daymare Cat is the ancestor of Slice of Sea, one could even say that it was the foundation of Seaweed’s game. Cat is the OG.

~

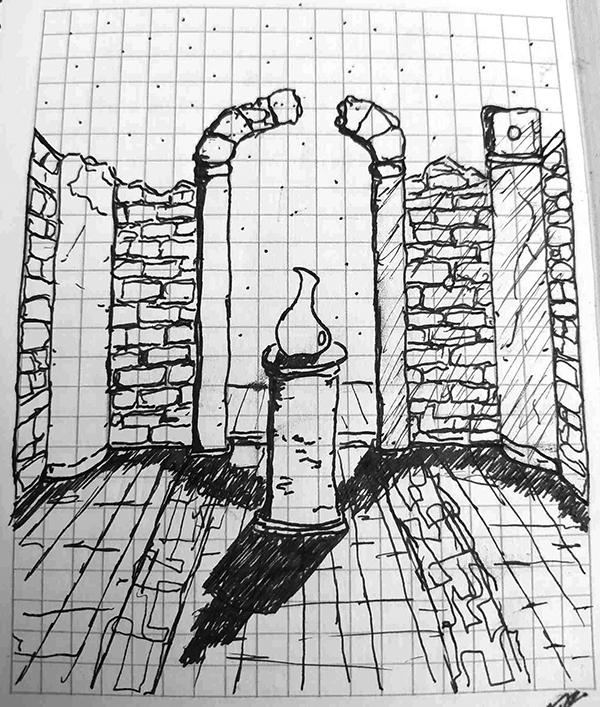

This game needed some major upgrading, since its release my gamedev art direction and workflow changed drastically. Things that are new in this Anniversary Edition:

- The game is in glorious 60 fps and plays in full screen.

- Most noticeably the game has new background texture. This might be a bit controversial take, but in my opinion this improves the vibe.

- Interactive items have a color. Yes. A color.

- Cat now runs like a ballerina, not a raptor. Thank god.

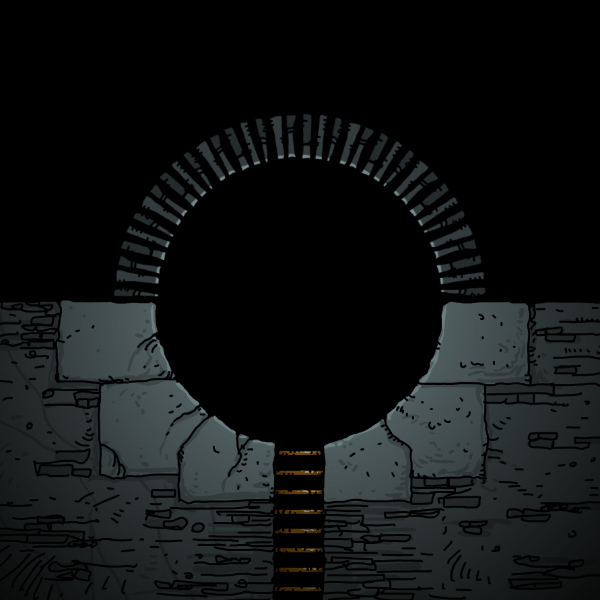

- Platforming is a bit easier thanks to hitbox tweaking but also by redrawing platforms in few places, for reference check the main gate.

- I added a new pathway for you in case you have a fear of being eaten alive by a cosmic horror monster and really don’t want to do this part. So now you can go around it.

- No changes were done to the music, since it’s already perfection.

~

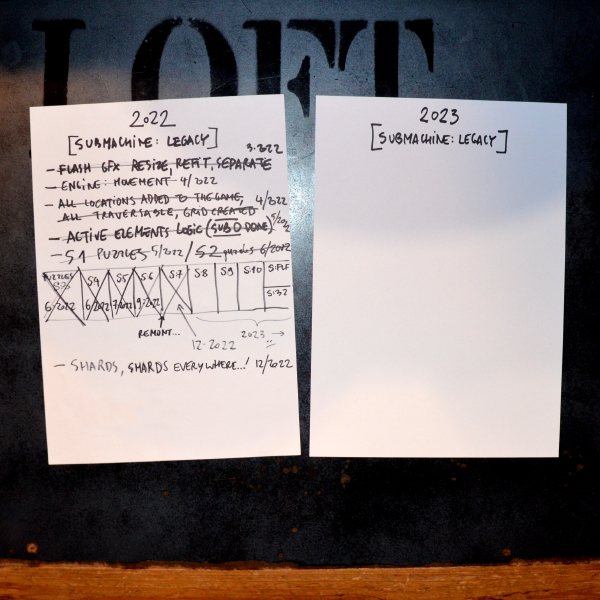

Meanwhile, a year later:

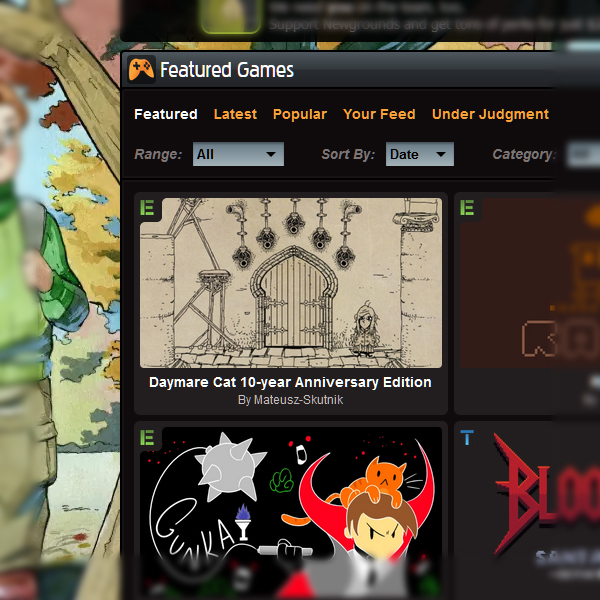

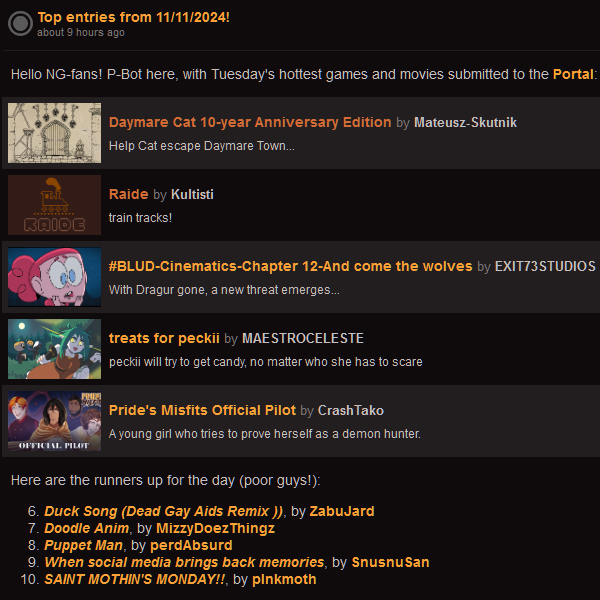

Oh, I completely forgot to upload this game to the OG flash portals, Newgrounds and Kongregate. Uploaded them on November 11th 2024. Our independence day. The 3rd anniversary of release of Slice of Sea.

Results after 24 hours:

On Newgrounds:

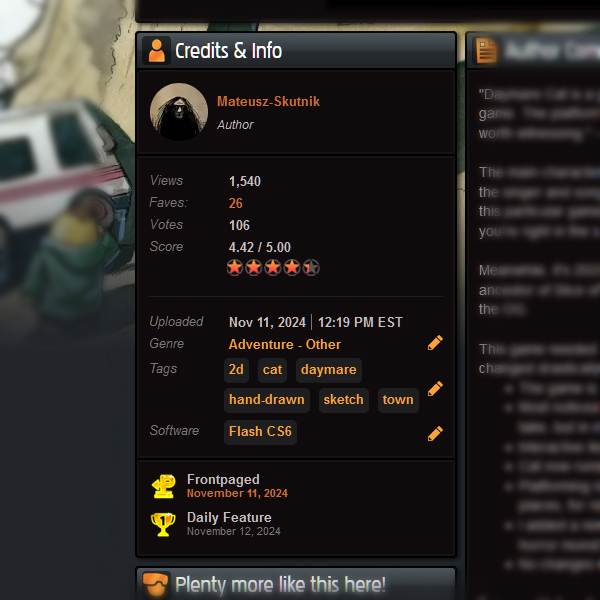

- Frontpaged November 11, 2024

- Daily Feature November 12, 2024

- Views 1540

- Faves: 26

- Votes 106

- Score 4.42 / 5.00

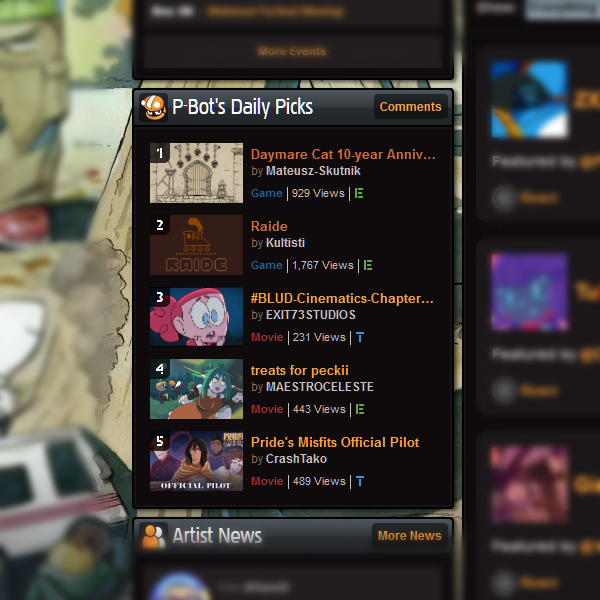

- P-Bot’s Daily Pick

While on Kongregate:

- Publishing this game requires approval. Please make sure it meets all the requirements for submission by going through our Submission Checklist. Once the game is ready, submit it to [email redacted] and make sure to include your Kongregate username and the title of your game.

Lol. :D